Ink as Water, Plate as Sky: The Lost Tradition of Subtractive Monotype

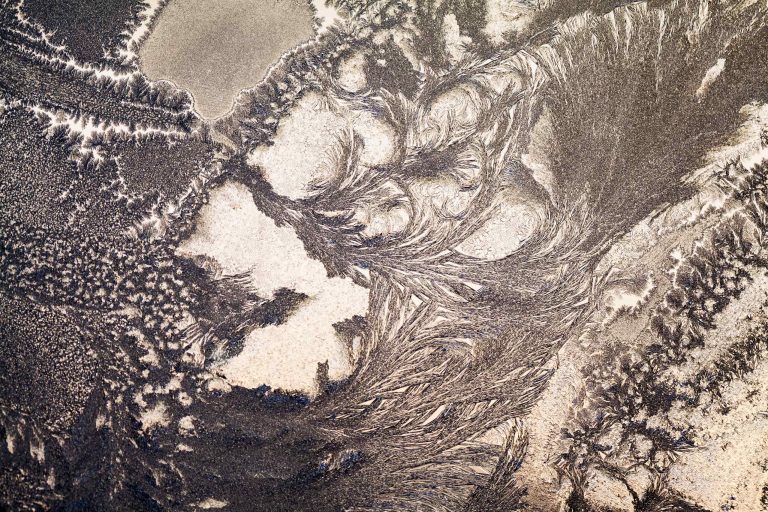

We usually think of monotype as additive: roll ink, then draw on top. Lines appear where we place them, darkness accumulates where we press harder. Yet the most luminous monotypes in history were born from the opposite gesture—subtraction. The plate begins completely covered in black, and the image emerges only where ink is removed.

Old masters called this working “from the dark into the light.” Rembrandt experimented with it on copper. Degas made it sing on paper plates. Today it feels almost forgotten, yet it remains the fastest way to achieve atmospheric depth and impossible softness.

Start with a smooth acrylic or glass plate rolled edge-to-edge with dense, velvety ink. The surface should look like a night sky with no stars. Then, instead of drawing, you begin erasing the night.

Tools become gentle:

- A scrap of silk lifts broad veils of tone.

- The blunt end of a brush handle carves rivers of light.

- Fingertips pressed lightly create clouds.

- A single cotton bud can suggest an entire horizon.

Every subtraction is permanent. There is no going back to add darkness once it is lifted. That risk is what makes the method intoxicating. Light feels earned because it was stolen from absolute black.

The results have a quality no additive method can match:

Mysterious gradients that look airbrushed but are made by hand Edges that dissolve like breath on cold glass Figures that seem to materialize from fog

A simple practice to feel the difference:

- Divide one plate in half with a strip of tape.

- Left side: work additively—roll thin ink, draw with dark tools.

- Right side: roll thick black, subtract everything that should be light.

- Pull both sides on the same sheet of paper.

Stand back. The subtractive half will almost always feel deeper, older, more alive. It carries the memory of darkness even in its brightest passages.

Subtractive monotype also teaches restraint better than any instructor can. When every highlight costs you real estate on the plate, you learn to leave vast areas untouched. Silence becomes as important as sound.

Some of the most moving prints I have ever seen were nearly empty: a single subtracted moon floating in black, or the faint outline of a hand disappearing into ink. The viewer’s eye completes what the artist refused to state. That collaboration is the highest form of generosity.

Next time you feel your prints growing heavy and overworked, cover the plate completely and walk away for five minutes. Return and begin removing. Do not plan. Simply uncover what wants to be seen.

You will be astonished at how little you actually need to say when darkness itself becomes the co-author. The night will do half the work for you.